PHILADELPHIA (September 28, 2020)—In a study published today in the prestigious journal Cancer Cell, researchers at Fox Chase Cancer Center showed how altering lipid metabolism may contribute to sustaining tumor growth in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. The finding could help overcome a major problem in pancreatic cancer treatment resistance and metastatic spread, the researchers said.

“The initial assumption was that if we block biosynthesis of cholesterol in cancer cells, that should prevent cancer development,” said Igor Astsaturov, MD, PhD, the study’s lead author and an associate professor in the Department of Hematology/Oncology at Fox Chase.

But they were not able to prove the hypothesis, Astsaturov said. Instead, the researchers found something entirely unexpected. Typically, epithelial tumors, such as pancreatic, grow in clusters that mimic normal glands. When cancers become aggressive, they begin to grow in sheets resembling fibroblasts. This effect is known as epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which is the hallmark feature of a subtype of pancreatic cancer known as basal.

Using mouse genetic models of pancreatic cancer, the researchers found that when cholesterol biosynthesis was blocked, the cancer switched its growth pattern and acquired the molecular features that changed it from glandular to basal subtype.

“These basal tumors are inherently treatment-resistant and aggressive,” said Astsaturov. “We think that we’ve identified a new metabolic regulator that can promote the EMT and the basal conversion. This is a major obstacle for anticancer therapy that is responsible for chemotherapy resistance and metastatic spread.”

When the researchers investigated why the phenotype switch occurred, they found that when tumors are deprived of lipids, they activate a transcriptional factor called SREBP1. Activated SREBP1 induced the expression of a secreted growth factor, TGFB1, a key mediator of the EMT, during which the epithelial cells lose their ability to adhere to each other and become migratory.

Astsaturov said researchers investigated whether dietary factors or medications such as statins could be related to this change. “Working collaboratively, we found, quite disturbingly, that patients who take statins and have a lower level of blood cholesterol have a higher prevalence of the EMT cells in their tumors,” he said.

“If someone has pancreatic cancer and low blood lipids due to poor nutrition, and takes a statin, this is not a good combination because it may promote the conversion to a more aggressive subtype of pancreatic cancer,” he added.

To gain greater clarity into the relationship between diet, medication, and pancreatic cancer aggressiveness, Astsaturov and colleagues are now beginning to look at a larger collection of human samples to determine how blood lipids correlate with a patients’ nutrition, medicines they are taking, and the percentage of EMT cells in their tumors.

“Essentially, what we are looking for is whether there is an association between cancer aggressiveness and having poor nutrition, low blood lipids, high level of insulin, or anything that activates SREBP1,” said Astsaturov.

The study is a complex, multifaceted investigation that involved collaboration between numerous Fox Chase scientists and other collaborators across the United States. The first author, Linara Gabitova-Cornell, PhD, is a postdoctoral associate in Astsaturov’s lab.

Other Fox Chase researchers included Edna Cuikerman, PhD, co-director of the Marvin & Concetta Greenberg Pancreatic Cancer Institute; Erica Golemis, PhD, co-leader of the Molecular Therapeutics Program; Carolyn Fang, PhD, co-leader of the Cancer Prevention and Control Program; Elizabeth Handorf, PhD, an associate professor in the same program; and Suraj Peri, PhD, an assistant research professor.

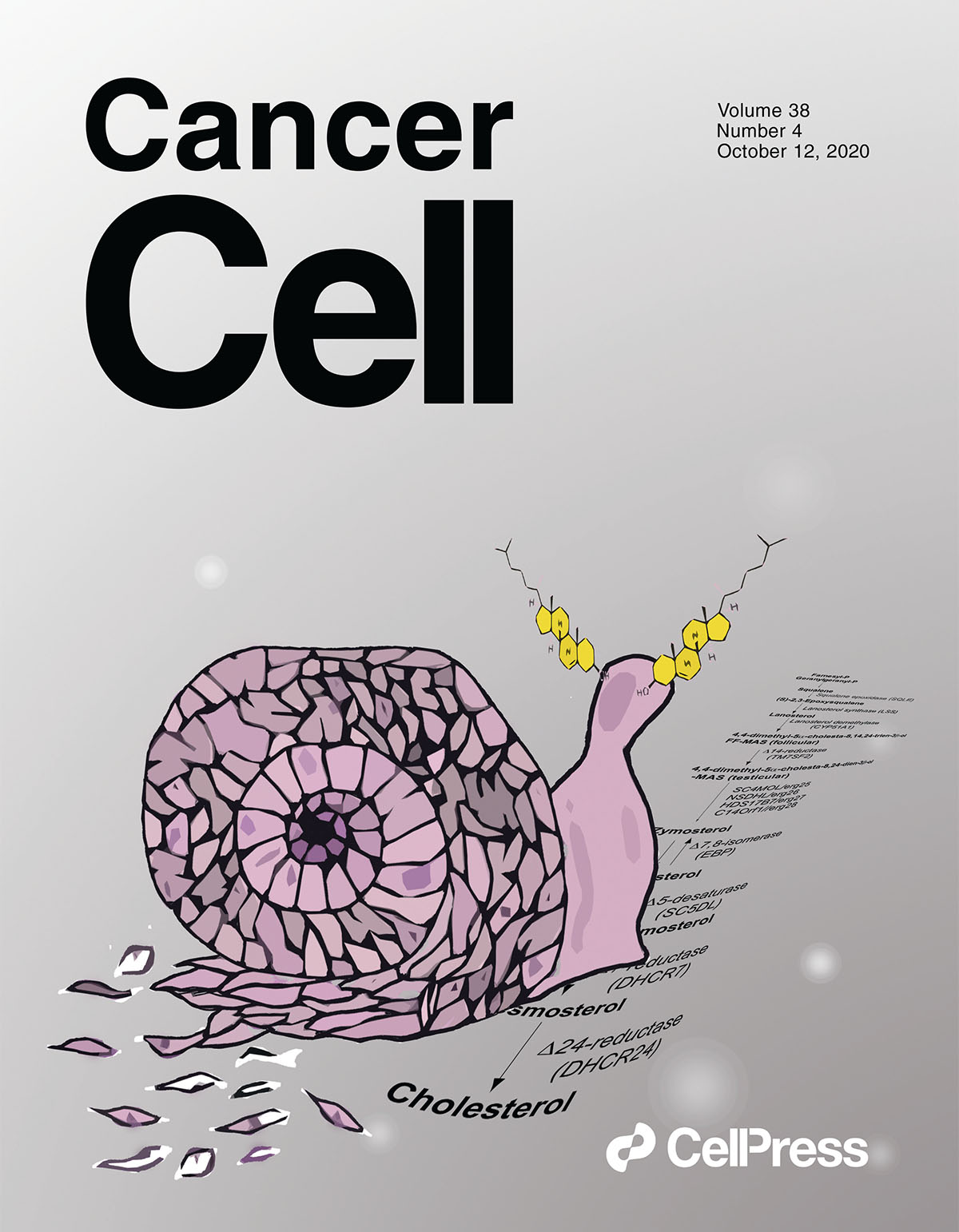

The study, “Cholesterol Pathway Inhibition Induces TGFβ Signaling to Promote Basal Differentiation in Pancreatic Cancer,” was published in the journal Cancer Cell.