Colorectal Cancer: Does Your Family History Put You At Risk?

-

Updated 2/26/2021

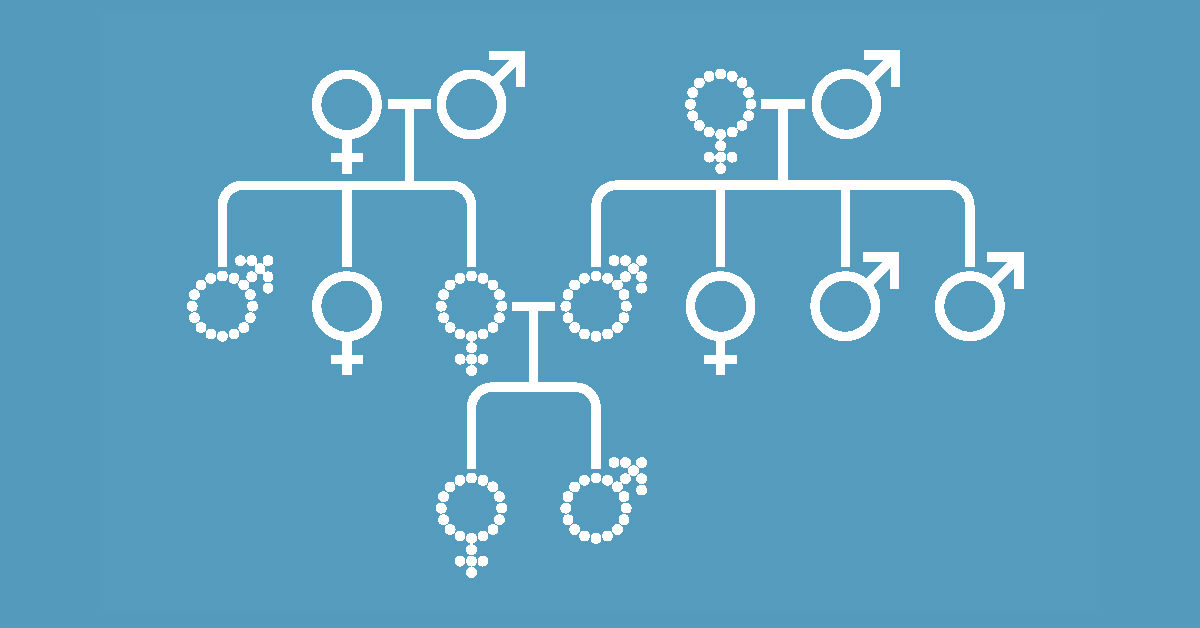

When it comes to understanding your risk of getting colorectal cancer—a leading cause of cancer deaths nationwide—a valuable consideration is your family history of the disease. As many as 1 in 5 people who develop colorectal cancer have other family members who’ve had it.

“That’s why it’s crucial to learn about your family history of colorectal cancer and to share that information with your healthcare provider,” said Michael Hall, MD, MS a gastrointestinal oncologist and clinical cancer geneticist at Fox Chase Cancer Center.

A strong family history may indicate you need to begin colorectal cancer screening earlier than the typically recommended age of 45, and you may need to be screened more frequently. Most colorectal cancers start as abnormal growths called polyps that can turn into cancer. “Screening can help doctors find and remove these pre-cancers, which prevents cancer from ever developing,” Hall said. By having polyps removed during a colonoscopy, you can reduce your risk of developing colorectal cancer back to a normal state.

Likewise, it’s important to tell your close relatives if you have colorectal cancer so they can pass on that information to their doctors and start screening at the right age.

What exactly is a family history?

Any family history of colorectal cancer raises your risk of the disease. But your risk can be even higher if you have a first-degree relative with colorectal cancer—that’s a parent, child, or sibling. Nationwide, about 1 in 20 people will be diagnosed with colorectal cancer at some point in their lifetime. “But having a first-degree relative with colorectal cancer doubles that risk to 1 in 10,” Hall said.

Consequently, anyone with a first-degree relative with colorectal cancer should start screening at age 40 and be screened every five to 10 years, according to guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). Like many cancer specialists at Fox Chase, Hall helps write NCCN screening guidelines for genetic colorectal cancer screening, which are recognized as a gold standard of cancer care.

Could you have Lynch Syndrome?

The most common inherited genetic condition that causes colorectal cancer is Lynch Syndrome.

This syndrome, which may affect roughly 1 out of every 300 people in the U.S., is caused by mutations in the genes involved in repairing DNA. And depending on which gene is affected, the disorder can raise the lifetime risk of colorectal cancer to as high as 80 percent.

Women with Lynch Syndrome also have a high risk of endometrial cancer. There are other cancers linked to Lynch Syndrome—including those of the ovaries, stomach, small intestine, kidneys, and pancreas.

Even so, the “vast majority of people with Lynch syndrome don’t know they have it,” Hall said.

One red flag is having a first-degree relative diagnosed with both colorectal cancer and another cancer linked to Lynch Syndrome—with one of those cancers occurring before age 50. Another is having multiple family members diagnosed with both colorectal and another cancer linked to Lynch Syndrome, at any age, or a first-degree relative diagnosed before age 50 with a cancer linked to Lynch Syndrome.

If you’ve already had colorectal cancer, your tumor should be tested to see if you might have Lynch Syndrome and are at risk for other cancers, Hall cautioned.

Should you see a genetic counselor?

If you’re concerned about your family history—or your doctor considers it worrisome—you may benefit from genetic counseling.

Overall, fewer than 10 percent of colorectal cancers are caused by gene mutations passed down from parent to child, research shows. But the younger your relatives were when they were diagnosed, the more concerning the family history.

In one study, 13 percent of people diagnosed with colorectal cancer before age 50 had a gene mutation associated with colorectal cancer.

An experienced genetic counselor, like those at Fox Chase, can review your family history and help you learn how likely it is that you’ve inherited an abnormal gene. “A counselor can also help you decide if genetic testing—done as a DNA blood test—is right for you,” Hall said.

Testing isn’t perfect. It may not always give you clear results. But if an abnormal gene is detected, “the good news is that you can take steps to protect yourself from colorectal cancer,” Hall stressed.

And if genetic testing reveals you have Lynch Syndrome, stepped-up screening for colorectal cancer and other cancers associated with this disorder can help you stay healthy.

“There’s tremendously high value in genetic testing if you may be at risk of inherited colorectal cancer,” Hall emphasized.

Learn more about genetic testing for colorectal or other cancers at the Fox Chase Risk Assessment Program.

Request an appointment with a clinical genetic specialist by filling out this form or calling 877-627-9684.