PHILADELPHIA (March 16, 2021) — The drug ibrutinib, also known by the brand name Imbruvica, can be an effective tool to slow or stop tumor growth in lymphoma, a type of B-cell neoplasia. But for patients who become resistant to the medication, there are a limited number of other options. Now, new research by Fox Chase Cancer Center physician-scientists opens the door for alternative treatments.

“We asked this question: ‘What makes some tumors respond to this drug and other tumors resistant to this drug?’” said Y. Lynn Wang, MD, PhD, FCAP, a professor in the Department of Pathology and the Blood Cell Development and Function program at Fox Chase.

Tumor cells have a molecular pathway that sends them a signal to keep growing no matter what; unlike healthy cells, they never get the signal to stop or shut down. At the same time, the microenvironment, which consists of the cells, molecules and blood vessels surrounding the tumor, promotes this growth, essentially feeding the tumor cells. Ibrutinib works by disrupting both of these processes.

“We knew that tumor cells rely on both pathways, but we didn’t know if there was a link between them,” Wang said.

B-cells are a type of blood cell that is key to the immune system. Lymphoma occurs when B-cell grow out of control and become malignant. Wang and Wenjun Wu, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Wang’s lab, used RNA sequencing to identify the genes controlled by B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling, the molecular pathway that tells tumors to grow. They also identified the constellation of molecules that connect tumor cells to the microenvironment that feeds them.

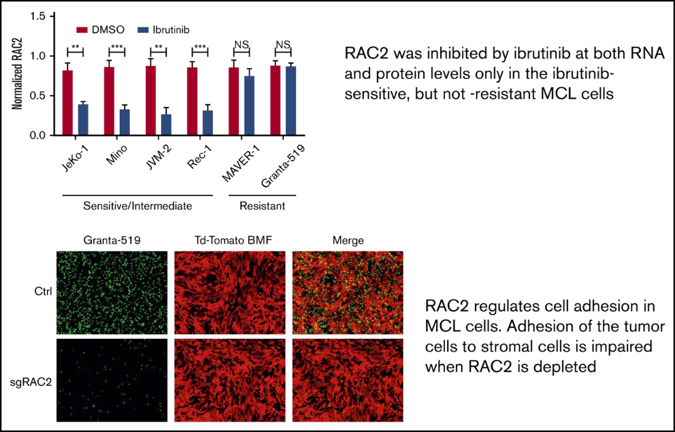

In collaboration with colleagues at other centers in the United States and China, they found that the two mechanisms were clearly linked. In tumors that were sensitive to ibrutinib, both BCR signaling and cell adhesion were suppressed. If the tumor was resistant, neither was affected. “The BCR signature and the cell adhesion molecule signature are coordinated,” Wang said.

And in a novel discovery, they identified the molecule that connects these two processes. The scientists showed that by knocking out or knocking down the molecule, called RAC2, they could prevent tumor cells from adhering to their microenvironment and thus slowing tumor growth.

“This is the first discovery of a new role of RAC2 in B-cell lymphoma,” she said. “RAC2 links these two processes together, and that means a tumor resistant to an inhibitor of B-cell receptor signaling, like ibrutinib, may be sensitive to an inhibitor against RAC2.”

As a next step, Wang wants to investigate whether the RAC2 molecule plays a similar role in other types of lymphoma. If it does, it could pave the way for the development of an RAC2-inhibitor drug. “Development of an RAC2 inhibitor may introduce a new way to sever lymphoma cells from the microenvironment, tackle lymphoma, and overcome drug resistance,” she said.

The study, “Inhibition of B-Cell Receptor Signaling Disrupts Cell Adhesion in Mantle Cell Lymphoma Via RAC2,” was published in Blood Advances.