Fox Chase Cancer Center Celebrates 50 Years Since the Discovery of the Hepatitis B Virus

-

Originally published in Forward, Spring/Summer 2017

By Paige Allen

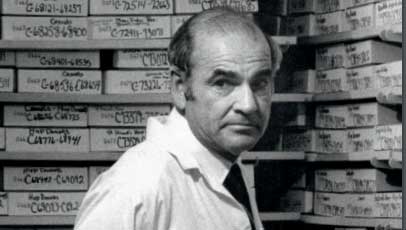

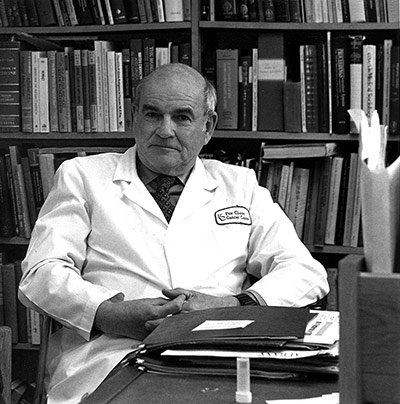

Scientists are seekers. Their inquiries may lead them to the far reaches of the world, or inward to incomprehensibly small molecular worlds. At a time before research on individual genes was possible, the late Nobel Laureate Baruch S. Blumberg combined these approaches, saving millions of lives.

With Fox Chase Cancer Center as his base, he traveled the world collecting blood samples from diverse populations to study genetic variations among humans. Fifty years ago, in 1967, he discovered the hepatitis B virus.

Hepatitis B can develop into liver cancer or cirrhosis, and can cause liver failure. The discovery of the virus was significant, but what Blumberg did next was unconventional and deeply impactful. He began developing a vaccine.

“He went straight from fundamental discoveries into an approach we now term translational medicine, which was an unusual course to take and far ahead of its time,” said Jonathan Chernoff, chief scientific officer at Fox Chase. “Barry was an unconventional thinker, one of those guys who went outside the boundaries of his discipline frequently and without embarrassment. He was an epidemiologist, a virologist, a molecular biologist, and more, who did whatever he needed to do to find answers.”

Blumberg and his colleagues prevented transfusion-related cases of hepatitis B by developing a sensitive blood test that allowed blood banks to screen for it. They also devised a way to make a vaccine, harvesting its outer protein from the blood of chronic carriers. This approach was critical, because the virus could not be grown in tissue cultures at the time. Meanwhile, on field trips to Africa and Asia, Blumberg and others amassed important evidence showing the link between primary liver cancer and hepatitis B.

The virus is now thought to cause at least 80 percent of liver cancers as well as many cases of cirrhosis. In 1981 the vaccine received Food & Drug Administration (FDA) approval. It was the first vaccine capable of preventing a type of cancer in humans. “That vaccine prevented between 10 and 100 million cases of liver cancer around the world,” Chernoff said. “It is probably the most effective cancer prevention agent ever devised, and had an impact the like of which we’d never seen before or since.”

Following the vaccine’s FDA approval, a number of nations launched vaccination programs in consultation with Blumberg and his colleagues. Targeted to infants, these prevention programs may have reduced the incidence of primary liver cancer by as much as 80 percent or more in future generations, and they are credited with preventing millions of cases of acute and chronic hepatitis.

The combination of the discovery of the hepatitis B virus and the vaccine development led Blumberg to win the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1976. “The discovery and the vaccination made a huge difference in livelihood for many people,” Chernoff said. “His work transcended science into general culture.”

In 1993, Blumberg and his co-inventor, Irving Millman, were elected to the National Inventors Hall of Fame for their invention of the vaccine and diagnostic test.