Breast MRI: A good study, but not everything we hoped for

-

There is probably no imaging study that is more controversial in the care of patients who have breast cancer or other breast problems than breast MRI, which has been around for 30 years.

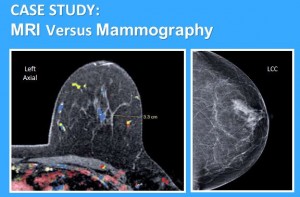

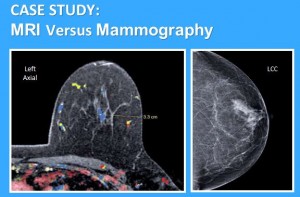

This imaging study is more sensitive than mammography and detects the size of cancers more accurately than other breast imaging. Sounds promising, right?

The medical profession has had high hopes for breast MRI when used before breast cancer treatment, but after much research, it’s not everything we have hoped for, and the controversy abounds. It is indeed more sensitive than mammography, ultrasound and PET scans, especially for small cancers, but that sensitivity comes at a price. Imaging studies that are more sensitive end up being less “specific,” meaning that while they detect many more things, they cannot differentiate as well between the types of things they’re detecting. Is it a cancer, a benign breast finding, or a false positive (meaning that there’s nothing really there at all)? Such ambiguities lead to unnecessary tests, biopsies and even extensive surgeries to determine exactly what it’s showing us.

As mentioned earlier, breast MRI is also better for estimating the size of cancers, and we have assumed that breast MRI should help us with the surgical component of breast cancer treatment by giving us a clearer picture by which we can cut out these cancers more completely. But, disappointingly, multiple studies and prospective trials worldwide have found that surgeons inadvertently resect cancers incompletely just as often when we have an MRI to look at for surgery, as when we don’t have one. This is, in part, because while MRI is better than mammography, it still is far from perfect. It can overestimate a tumor’s size, underestimate a tumor’s size, and in some cases doesn’t even see small amounts of tumor at all.

The second reason for the lack of benefit is that the breast is soft and malleable, and not hard and rigid. When a mammogram is taken, the breast is compressed in one direction and spreads out in the opposite direction. With an an MRI, the patient is lying face down in the machine while the breast hangs into the MRI coil uncompressed. During surgery, the patient lies face up, while the breast flattens slightly against the chest wall – exactly the opposite position of the MRI. These differences are probably substantial enough to change the apparent distance between the cancer and the borders of the breast, thus eliminating any advantage in clarity that the MRI has when the surgeon tries to cut out the tumor.

There are specific situations when MRI is indeed helpful because of tumor biology. These include women who are high risk to develop breast cancer including those with a known gene mutation, women who have Paget’s disease of the breast, and women who have cancer in the lymph nodes, but no primary tumor in the breast found on mammogram or examination.

So like every test, be aware that breast MRI is not appropriate for everyone even though it can be helpful in particular situations. I encourage patients to talk to their cancer professional about whether the study will do more good than harm, or more harm than good. Because while it’s a good study for certain situations, it’s not everything to everyone.