Fox Chase Born of Merger

-

Maddy Weber

Originally published in Forward, Fall 2012Becoming ‘comprehensive’ meant melding of cultures

Just 40 years ago, the Fox Chase Cancer Center of today—a place known for providing top-level patient care and conducting cutting-edge research—was merely an idea. As Fox Chase transitions into its role as a member of Temple University Health System, it’s worth remembering that the Center was formed by a similar integration not so long ago.

The concept of the comprehensive cancer center—a facility where treatment and research are united under one roof—came into being when Richard Nixon signed the National Cancer Act in 1971. Widely known as the launch of the “War on Cancer,” the act included funding for a series of such centers.

At the time, prominent cancer research institutions the country over, including Philadelphia’s own Institute for Cancer Research, began to scout for suitable clinical partners. Once merged with a hospital, they would be eligible to receive federal funds.

For the Institute for Cancer Research, the natural choice for a collaborator was the American Oncologic Hospital—one of the oldest cancer hospitals in the country, having been founded in 1904. After decades of struggling to find larger quarters, the organization had moved to the Fox Chase section of northeast Philadelphia—right next to the institute—in 1968.

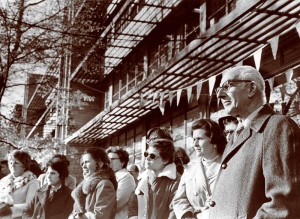

The Institute for Cancer Research joined forces with American Oncologic Hospital in 1974 to form Fox Chase Cancer Center. Employees watch the groundbreaking for the structure now called the Center Building, which would physically connect the two entities. After several years of planning, the two institutions merged in late 1974 and became one of the country’s first National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer centers—and received a chunk of the coveted financial support.

“I welcomed the measure when I found out that we were going to join with the hospital,” says Jenny Glusker, a chemist who came to the institute in 1956 and continues to conduct research on the structures of chemical carcinogens and cancer treatments at the Center.

Glusker and her colleagues were no strangers to collaboration. The researchers often had attended seminars at the hospital and shared ideas with the hospital staff in the years leading up to the merger. Glusker also had collaborated with hospital radiologists to use computers to generate three-dimensional images of the human body and create models of crystal structures—work aimed at shedding light on the biological processes that underpin many cancers.

But the move was less welcome for some other staff members, who found themselves facing a variety of compromises—of space, of resources, and perhaps most importantly, of culture.

“It was clear to me that many of the scientists considered the hospital to not be sufficiently staffed or credentialed,” says Paul Engstrom, a physician-researcher who came to the hospital as director of medical oncology in 1970.

“When you juxtapose the institute with the hospital, there were some rough spots,” Engstrom adds. “We had three full-time medical oncologists and no full-time surgical oncologists. Stack that up against the institute, which had already been in Fox Chase for 30 years and had a very well-known group of scientists.”

Beyond staffing concerns, there were intangible differences that needed to be weighed.

“It was a clash of cultures,” Engstrom says. “Physicians are used to treating patients and want results right away. Scientists, by and large, are looking at the long term. It might take years to get results.”

Chief operating officer Gary Weymuller, who came to Fox Chase in 1977 as human resources director, recalls the discordance. “There were two sets of dynamics going on. From a cultural perspective, the staff at the institute was more independent and, being driven by the scientific method, more apt to question and challenge new things. Hospital staff members were more regimented. They were used to answering to regulatory agencies and were more willing to accept changes they were told were necessary.”

A transformation was germinating, however, and Weyhmuller says that eventually the hospital and the institute began to feel less like distinct organizations and more like what they had become—a single comprehensive cancer center.

What’s more, the merging of treatment and research in one facility paved the way for the current scientific era, in which, as Engstrom says, “the emphasis is on collaboration and clinically relevant research.”

In the wake of the merger, collaborations between physicians and scientists began to increase. Today, the Center is known for turning out a high level of cancer research, both “basic,” or undertaken to increase the understanding of fundamental principles, and “translational,” or more immediately applicable to medicine.

As Fox Chase faces a future as part of Temple University Health System, Weyhmuller says that the principles of dealing with change that applied in the 1970s still hold true: “People’s tendency is to say, ‘No, we’ve always done it this way,’” he says. “I’ve always kept an open mind and said yes when someone asks, ‘Can you take this on?’ And when I look back, I realize it was a good decision.”